by Lesley Younge

In his book, How to Raise An Anti-Racist, Ibram X. Kendi says, “The first lesson American children usually receive on racism is that it is unmentionable… What if kids were instead more systematically taught about racism at the moment they are starting to see it themselves? What if we started by teaching third-graders about the racial inequities that they are already starting to notice — or that affect their lives? What if we taught these racial inequities as the problems that society needs to fix?” In other words, what if we talked to our children openly and honestly and told them the truth?

Caitlyn Barr Atkins and I are co-leads of the MoCoLMP Education Committee. During our presentations to local schools and conferences, we discuss MoCoLMP’s community projects and how classroom teachers can connect their curriculum and learning goals to this difficult history. We note the ways our local public school district, MCPS, has taken steps to offer materials to K-12 teachers as part of Remembrance Month.

Because the connections to history classrooms can feel more obvious, our focus has been on expanding the scope of which teachers think of these stories as part of their domain of responsibility. We encourage English teachers to explore thematically related poetry, literature, and nonfiction texts that also align with our reading and writing objectives.

These are some of the guiding principles that help us prioritize teaching the truth and turning our classes into anti-racist spaces. We find they guide us as parents in talking to our own children as well.

To teach the truth, lean in.

Something I learned from my mentor, Monica Edinger, the co-author of our book Nearer My Freedom, is to lean into teaching hard history. We met as fourth-grade teachers at The Dalton School in New York City. Our social studies curriculum was a year-long study of immigration and the development of diversity in America, which included a unit on the transatlantic slave trade. A challenging topic to cover with any developmental age, we focused on stories of resistance and learned about the captured Mende of the Amistad who fought back physically, Ona Judge who ran away from George Washington, and the Gullah of the Sea Islands who preserved their West African customs and culture. We always started the unit by establishing a respectful understanding of the rich cultures from which people were torn away.

This was where I first met Olaudah Equiano, the subject of Nearer My Freedom.

Our culminating project was creating found verse about the experiences of captured and enslaved Africans from an adaptation of his autobiography. This project inspired the structure of our book, which we hope is a catalyst for conversation as well. Literature and poetry were faithful guides through the study of a very difficult period of history. For some of our 9- and 10-year-old students, these were their first in-depth conversations about racial oppression. It was not always comfortable or easy. On the other side of learning about the cruelty of the slave trade was deeper empathy for those impacted and a greater understanding of how human choices shape the world. They could handle it and so could we.

To teach the truth, have many conversations over time.

No matter the social justice topic, true understanding is likely to take several conversations that happen over time. Some children came to our study of slavery with a lot of information. For others, it was the first time they were really discussing this terrible history. Now I teach 7th grade and they are much more prepared to talk about a topic like lynching, which I teach during our unit on To Kill A Mockingbird. How we teach this book has changed a lot over the years, but for me, it has become a logical segue to introduce our local history and the work of MoCoLMP.

For a child to understand lynching, a lot of conceptual layers need to be in place. They need to understand racism and how it divided American communities by the color of their skin. They need to understand how oppression works and the role fear and terror play in keeping a system of oppression in place. They need to have a concept of death and the horrific possibility of murder. They need to understand the basics of how a judicial system should work and what it would mean for a mob of people to take justice into their own hands. Before we jump into our discussion of lynching, I make sure these layers are in place and fill in any gaps. By creating a strong foundation of understanding and safe space to learn and ask questions, I am also preparing them for future learning and conversations.

To teach the truth, lean on books.

Books and literature are wonderful partners in this work. While some books may be appropriate for children to read on their own, others should be read jointly with a family member. It is important to read and preview books before giving them to children so that the adults also have the information and are prepared to answer questions.

SocialJusticeBooks.org is a project of Teaching for Change, a non-profit organization whose mission is to provide teachers and parents with the tools to create schools where students learn to read, write and change the world. They review books for their social justice content and create book lists by topic making it easy to search for the right title at the right time. Regular access to books about race and difficult history is important, and so is normalizing conversations about these topics. Instead of waiting for an outrageous incident in the news or community, incorporate them into the everyday. When incidents happen, young people may feel more mentally prepared and that can minimize harm and maximize their ability to respond in ways that are compassionate and empowered.

To teach the truth, incorporate local sites, museums, and art.

One of the reasons it has been important for MoCoLMP to install markers near the sites of our county’s known lynchings is to locate this history in our everyday lives. This is not a story about something that happened far away. It happened right here and the legacy impacts every community member, whether they know about the history or not. Our local markers become a site for remembrance and conversation. If you pass a marker with important history, don’t rush by. Stop, read it together, and talk about it. Answer any questions your child might have and if you don’t know the answer it's okay! Tell them they asked a very good question and you can research it together to find out more. Modeling the ways in which learning about history is an ongoing process is key. We cannot know it all, but we can stay open to finding out.

Other recommended books

Here are some other recommended books and podcasts to help support you on your journey to talk and teach the truth:

Rise Up Against Racism has a great list of podcasts, movies, books, and more.

Raising Antiracist Children is an interactive guide for

strategically incorporating the tools of inclusivity into everyday life and parenting. Britt Hawthorne offers lots of tips and activity ideas to make hard conversations a regular practice.

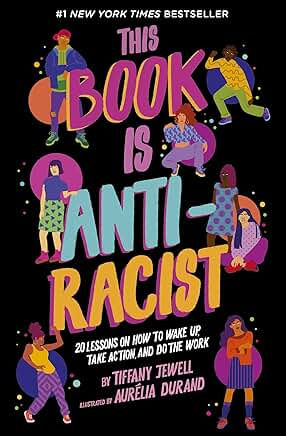

This Book is Anti-Racist by Tiffany Jewell is a terrific read for families and upper elementary or middle school-aged children. There are lots of helpful definitions and questions to guide conversations. There is also a family guide.

Lesley Younge and Caitlyn Barr Atkins are co-leads of MoCoLMP's Education Committee. Lesley shares, "For the second year in a row, we will present at the National Council of Teachers of English conference this fall. A highlight will be a keynote speech by Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and an inspiration for MoCoLMP’s work."

Comments